When we begin researching our family history, we often go to great lengths to steer clear of land records. We return time and again to censuses, vital records, and other people’s family trees, and find ourselves knocking against brick walls sometimes for years before we look to land records. My advice is always this: check out the land first. In the United States, recording of the sale of land began in the early 1600s in some areas, and include more individuals than any other type of record except our censuses. Land records include the original Application to the government for the land, a Warrant authorizing a survey to take place, a Survey or legal description of the land, any other requirements imposed, the ‘Patent’ or First Title recording the first time the land passed from government ownership to an individual, the Grant recording the first sale, and the Deeds, recording subsequent sales. Much information is packed into these documents, just waiting for you to find!Unlike records that track people, land records are an historical trail of what happened to the land, which brings several benefits to mind:

- They are easy to find, because for the most part, they are kept where the land is. Find the state or county where your ancestor lived, and you will find the land record.

- Except in cases of fire or flood, land records in a given county will be preserved from the origin of that county to the present

- Even in cases of fire or flood, the counties make an extraordinary effort to recreate destroyed records

- These records are public information and you have a right to access them

- They are kept in logical order: they are catalogued according to the date when the change of ownership is presented.

What Do You Need to Know to Begin?

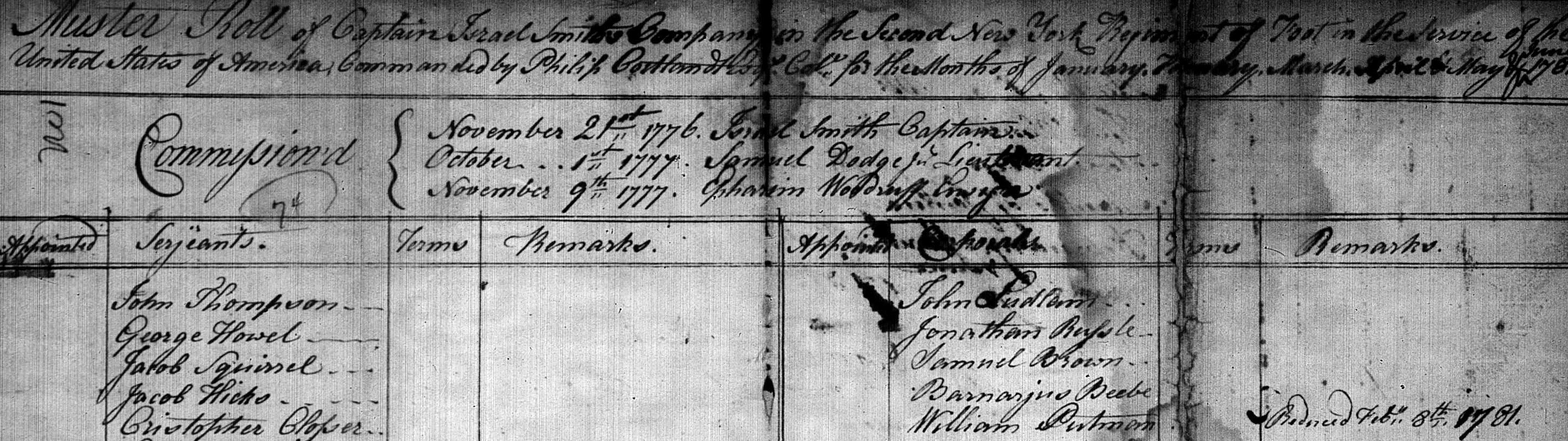

Two kinds of land records exist: public land records, held nationally, and state land records, held at the state and/or county level. Public Land Records: Except for the original 13 colonies that became states after the American Revolution, all the land in the US originally belonged to the federal government. Consequently, if your ancestor did not live in one of the original colonies, that person would have petitioned the US government to acquire land, and you should begin your search for records at the Bureau of Land Management (the new version of the General Land Office) and the National Archives. Here is a useful url: https://glorecords.blm.gov/default.aspx

State Land Records:

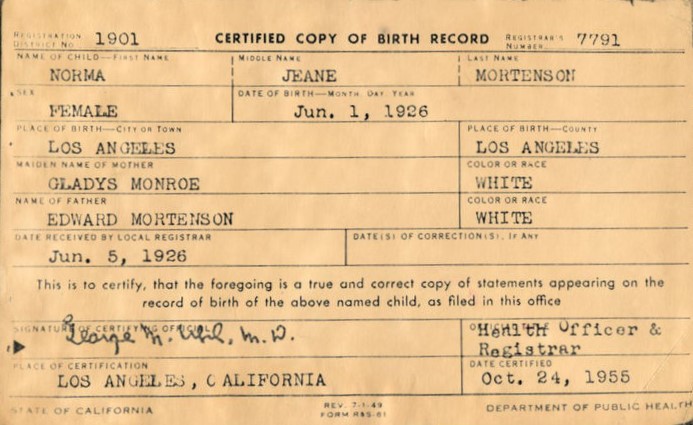

If your ancestor did live in one of the original colonies, you should begin your search at the state/county level, as those colonies retained the authority to distribute their own state’s land. Later, a few other states retained this authority, and those include Maine, Vermont, Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Hawaii. These records will be kept at the State Archives or in the County Recorder Office, depending on the archiving practices in the particular state.Now that you know where to look, you will need to be familiar with the words used on these documents. Here are a few basic definitions: A grantor is the person selling the land. A grantee is the person buying the land. A direct index is the list of the grantors, and an indirect index is the list of the grantees. A relict is the surviving spouse. A bounty land grant is payment given to an individual who served in the military, usually at the end of a particular war. Donation lands were properties sold cheaply, or donated for free, in order to encourage people to settle in new areas. Homestead grants were given to people with the caveat that they live on the land and make improvements to it for five years. Once this occurred, they would receive the patent for the land from the government. Sixty percent of people trying to obtain land via Homestead Grants failed to do so, but even rejected applications are maintained and the files are available to you, the public.

What Can You Learn From Land Records?

Now that you have a basic understand of what is there, why you might want to look, and what the terms mean, it is important to know that what you will learn from any document will go far beyond the name of the Grantee and Grantor. These documents often named the spouses and children of those participants. Occupations were usually listed in some form, as well as citizenship status and where the Grantor moved after the sale. Witnesses were required to execute documents, and the witnesses were often neighbors or family members, thus placing whole groups of people in time in a particular locale. This can be extremely useful during the years between the 10-year censuses, because every time a piece of land changed ownership, it underwent this process.Land records as a tool of genealogical research will open doors for you into vast records of people and places that you might never have imagined!