Genealogy has become one of the world’s most popular hobbies. USA Today noted that genealogy was bested only by the number one hobby of gardening. In terms of Internet searches genealogy is second behind (regrettably) pornography. It’s no wonder genealogy research has become such a popular pursuit with popular television programming like “Who Do You Think You Are?”, “Finding Your Roots”, “Genealogy Roadshow” and more. Ancestry.com and similar sites have ballooned into a multi-million (or try BILLION) dollar industry. The advertisements seen on television and across the Internet, coupled with the success stories depicted in these shows, have piqued the interest of millions of people around the world. After all it sounds so easy – like magic almost – given the “happy endings” featured in the various genealogy television programs. What is not depicted in these shows, however, are the hours of behind-the-scenes research which must take place in order to deliver those “happy endings”. I hate to say it but so many these days are gullible enough to believe they can discover their family history in a relatively short period of time, just like they do on television. If you are a serious and sober-minded genealogist, you are aware that’s quite unlikely to happen. There are no magic solutions, nor are there web sites which will reveal each and every detail of each and every one of your ancestors. Remember the old adage: “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is”? The same can be said for websites claiming to sell access to databases “you can’t find anywhere else” or quick solutions to your genealogical “brick walls”. These sites, however, are likely to be a total waste of both your time and hard-earned money. Similarly, beware of sites which claim to sell things like your family’s entire history, the history of your family name, or even in some cases a “fake” family crest or coat of arms. These days genealogical fraud is manifest in a number of ways, including identity theft. Here are a few examples:

Genealogical Research and Identity Fraud

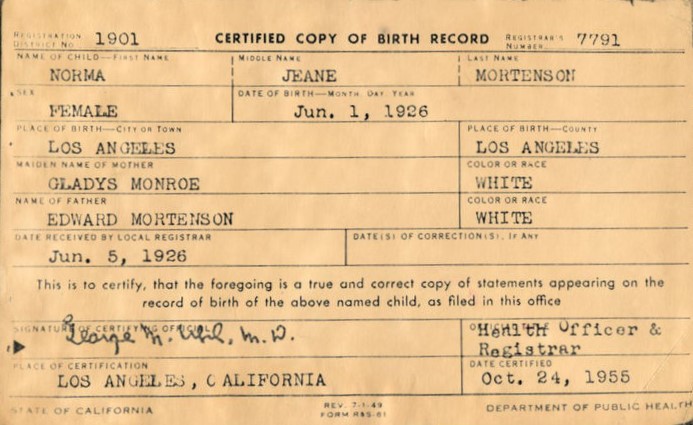

In 2012 news broke of an identity theft ring operating through a paid subscriber to Ancestry.com. The woman was mining information from birth records and the Social Security database, primarily selling them for the purpose of filing fraudulent tax returns. Changes were made and now only Social Security numbers of persons who have been deceased ten years or more are accessible on the site. It can sometime take months (or years) for government agencies to discover and address fraud in whatever form it manifests -- be it medical, Medicare, welfare and the list goes on. If you have chosen to make your family tree public on sites like Ancestry.com, be sure and privatize the records of living persons, especially birth dates.

Family Crests and Coats of Arms

One of your ancestors may indeed have been legitimately granted a coat of arms, yet today many web sites seem to imply surnames are attached to these noble symbols. Simply not true. According to the College of Arms in London, there is no such thing as a “coat of arms for a surname”. They point out that many people with the same surname can be entitled to entirely different coats of arms, while some people with the same surname (or perhaps a variation) aren’t entitled to one at all. Furthermore, they point out that coats of arms belong to individuals who have had it granted to them or descendants of the legitimate male line of a person previously granted one. It must be confirmed to be legitimate. And, it’s not that American citizens cannot be entitled to a coat of arms. It depends on whether an American can show proof of descent from a subject of the British Crown or some other royal entity. A popular misconception exists that the term “family crest” is the same as the entire coat of arms. The crest is “a specific part of a full achievement of arms: the three-dimensional object placed on top of the helm.” Thus, those companies who claim to sell your family crest may or may not be on the up-and-up. Caveat Emptor.

Finding the Cherokee Princess in Your Family Tree

Everyone who has actually found a Cherokee princess in their family tree, raise your hand. Hmm . . . I didn’t think so, but why is that? Primarily, it’s because there was no such thing as a Cherokee or Indian princess. Orrin Lewis, a Cherokee, has some observations: “Princess” may be a very poor translation for the chief’s daughter.” Remember, Cherokee chiefs were not kings, but rather chosen by their tribe or community. Lewis muses that perhaps the “mis-translation” may have been the result of American fascination with royalty, or as he called them “romantically-minded white people.” “Princess” may also have been a poor translation for an important female politician, peace chief or “Beloved Woman.” Again, these would have been elected positions and not inherited. Should you have such a person, Lewis suggests you not use the term “princess” for such an obviously “interesting and powerful woman.” The term may have been used by ancestors who married Indian women, hoping to alleviate racial tensions or stigmatization. In fact, men who married Indian women may have referred to their wives as Cherokee simply because the Cherokees were considered more civil than most tribes. It’s entirely possible that an ancestor referred to as an Indian princess may have actually been African-American. Lewis related the experience of one family researcher who had discovered that the term was sometimes used derogatorily in the South for light-skinned Mulatto women (e.g., “light yellow”).

Beware of Past Incidences of Genealogical Fraud

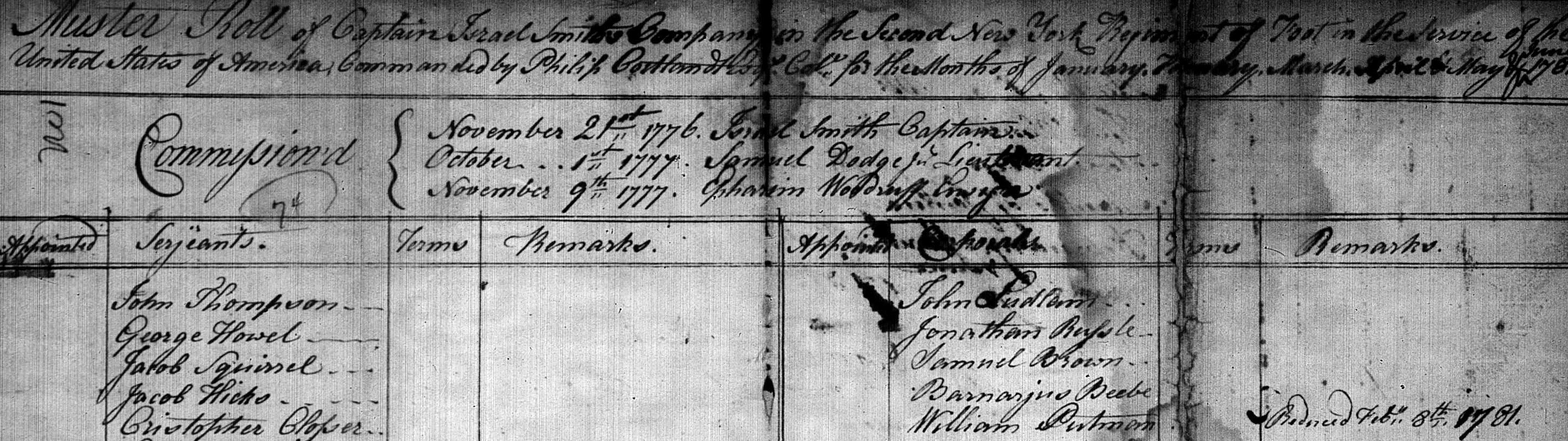

Not intending to throw a “monkey wrench” into anyone’s long and relentless pursuit of family history, but I draw attention to another important thing to be aware of: blatant genealogical fraud which occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It’s still possible these genealogical hoaxes have crept into our own research today. Harriet de Salis was a British authoress (publishing under the name “Mrs. de Salis”) of numerous books in the late nineteenth century. She was well known for a variety of published cookbooks and it appears she fancied herself an expert on an array of other subjects such as raising dogs (Dogs: A Manual for Amateurs, 1893) and poultry (New-Laid Eggs: Hints for Amateur Poultry-Rearers, 1892). Her book, The Housewife’s Referee, was a “treatise on culinary and household subjects”. Mrs. de Salis also had a rather short career in the field of genealogy. In the 1870’s she began sharing tidbits of genealogical “research” which came to be recommended by one of the most distinguished resources for early American ancestry, The New England and Genealogical Society. Harriet had formerly worked with Joseph Lemuel Chester, who although born and raised in America, left the country and settled in England in the late 1850s. Chester embarked upon a career in genealogical research after receiving a commission from the United States government to research wills recorded in England prior to 1700, thereby contributing vital research data concerning early American ancestry. Joseph Chester was the person who eventually revealed the de Salis deception after she confessed to him she had fabricated at least two wills. By 1880, Mrs. de Salis’ genealogical career was over and eventually her fraudulent claims were corrected. Meanwhile, back in America, Horatio Gates Somerby (1805-1872) was subtly perpetrating a similar fraud. Somerby wasn’t necessarily attempting to link various family lines to famous or noble ancestors. As Paul C. Reed noted in his 1999 article published in American Genealogist, Horatio Gates Somerby was “not necessarily better at fakery than Mrs. de Salis.” Still, Somerby probably thought he could get away with it because records were far less accessible than they are today. In 1976 American Genealogist identified some lesser-known genealogical fraudsters: C.A. Hoppin, Orra Eugene Monnette (founded of the Bank of America), Frederick A. Virkus and John S. Wurts. The history surrounding these hoaxes is fascinating, but one man’s genealogical hi-jinks deserves full treatment in next week’s concluding article: The King of Genealogical Fraud (which will also include a list of affected surnames).

This is Part One in this series. Click here to read Part Two.