Early religious records around the world are gold mines for genealogists as they seek key information that may not be found in civil records or newspaper resources (such as birth, marriage and death announcements) for certain time periods. People investigating religious records may find baptism, marriage, and death information in some denominations’ church records plus other useful connective information that may more fully illuminate the lives of ancestors. For example, aside from vital records information only, many churches were connected to early orphanages through records, and some churches’ minutes/reports on ancestor activities were especially thorough. Church newspapers also often provided information about ancestors that is not available elsewhere. We will look briefly at ways to find religious records for some Lutheran, Episcopal, Catholic, and Quaker ancestors in this article.

Lutheran Resource Example

The Card Catalog at Ancestry.com shows 132 entries for “Lutheran” in its collection titles. Let’s say you know that your ancestor, Lilly Gretha Anderson, was born in Texas about 1872 from other documents. However, that date was before states required birth records, and you want to research her exact birth date and her parents’ names. In “Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, Records, 1875-1940,” you can find her birth date of July 6, 1872 and a bonus of her baptism date, August 8, 1874 (an unusually long birth-to-baptism gap). Listed as her Swedish parents are Albertina Björkander and Hilder Yngve Anderson. This information turns out to be especially helpful because now that you have her parents’ names, you can learn can through newspapers that her mother died just a few months after Lilly’s baptism.

Episcopal Sources/Orphanages

Family lore tells you that she may have been placed briefly in an orphanage in New York City. Orphanages, new creations for the children of immigrants whose parent(s) had died, were often connected to churches. Thus, in New York City, if you follow religious affiliation leads connected to her Episcopal aunts who lived there, you can discover that Lilly entered The Orphans’ Home and Asylum for the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1876. With access to the church-related admissions records, you may learn that not only was Lilly in the orphanage briefly, but also discover that her Swedish immigrant cousin lived there as well, a new fact that helps flesh out other family lines. You will also find in the traditional church records these children’s first communions.Note: In this case, the orphan records are not held by the church, but are found instead in the extensive collections of the New York Historical Society. The Orphans’ Home and Asylum of the Protestant Episcopal Church in New York (records: 1851-1947) later merged into Leake and Watts Children’s Home records, 1802-1983.

Helpful Catholic Resources

Many Irish ancestors emigrated to Canada and America during the Great Famine era (1845-1852) when Ireland’s economy was in shambles. The early records related to them are contained in Catholic parish registers online at the National Library of Ireland. Irish emigrants generally emigrated to Boston, New York, and other Catholic areas, though not all Irish were Catholic. (Good news for researchers of Catholic ancestors is that Boston archdiocese records from 1789 to 1900 are being digitized currently at an expected cost of $1 million.) Putting together the family story for Catholics who married or had children during this era before civil records were required can be challenging for today’s American descendants. This is partly because some Catholic churches do not consider vital records “public.” Access varies. However, if researchers contact local libraries, historical associations, and dioceses themselves, they may often discover the critical church records from the 1850s-1870s that generally are not online. Dioceses such as that of Grand Rapids, Michigan have longtime archivists such as Fr. Dennis Morrow who goes out of his way to assist descendants with inquiries regarding marriages and births during during the 1850s-forward era. Dioceses such as those of Buffalo and Rochester, New York are also helpful. The Rochester Churches Indexing Project may help you find an ancestor’s name initially in its index. There you can see witnesses’ names, too, and often those witnesses were other family members. A new family discovery! If an ancestor’s name is there and you contact the local diocese, you may receive this kind of response, leading you onward to individual churches: “We do not maintain sacramental records in the Diocesan Archives. According to church law they must be held at the parish where the sacrament was received. The only thing I can do is to help narrow down the parishes you will need to contact. “ Seek original vital record information then through a parish, and also check for availability of connected Catholic newspapers such as the later (Rochester) Catholic Courier Journal (1945-1968) in the New York State Historic Newspapers Collection for additional information.

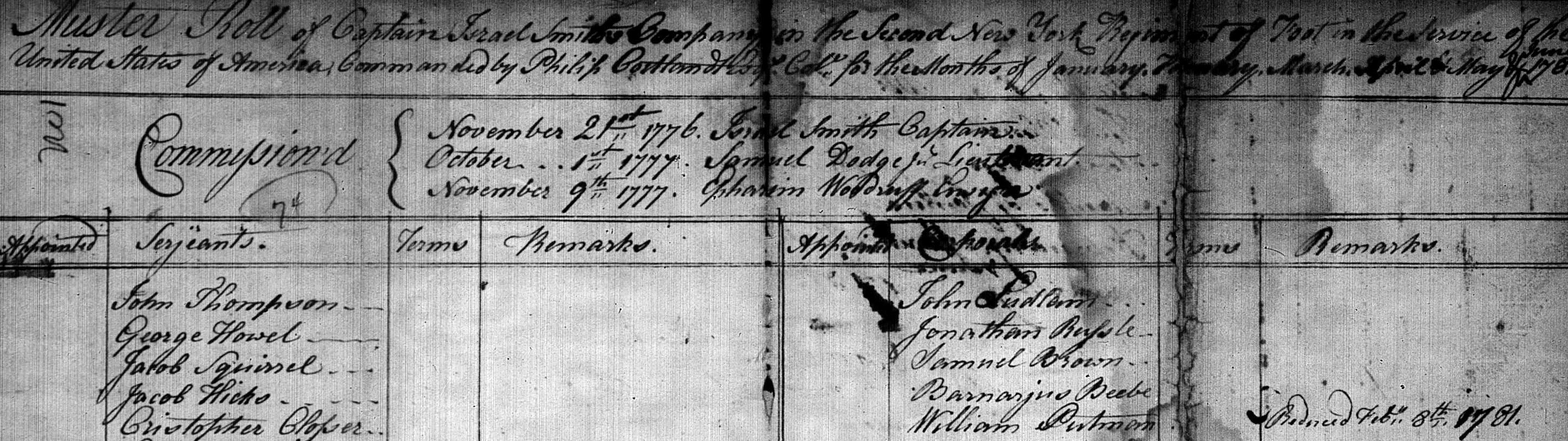

Quaker Records

For researching Quaker ancestors, FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com have helpful online collections, and numerous Quaker records are also found in separate repositories. In addition to vital record information, Quaker records have meeting times/people/activities listed that give us insights into our ancestors’ beliefs and daily lives. The Card Catalog at Ancestry.com lists 57 different collections for “Quaker,” butThe “U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935” is likely the most comprehensive for American Quaker ancestors. Look for several mentions – instead of just one – of Quaker ancestor marriage-related records because marital intentions were often repeatedly announced at subsequent meetings before a ceremony occurred. (Somewhat confusingly for modern researchers, “meeting” referred to both a congregation and to individual gatherings of male and female members separately, etc.)Helpful background in the Ancestry collection about how Quakers organized their congregations and meetings is included in source information for “Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Vol I-VI, 1607-1943.” You’ll learn there, for example, that Quakers had special ways of using date designations, how monthly meetings functioned, and how records were kept. This will help make the search for your Quaker ancestors’ activities and roles in the congregations more effective and enjoyable.